In the Year of Our Lord 1374, a deadly disease swept dozens of villages along the Rhine River — a dance plague. Hundreds of people on the streets jumped and curled their knees with no beat or music, except, probably, that in the dancers’ head. They danced, sometimes for many days in a row, until their broken feet refused to hold them. Many died of exhaustion, stroke or heart attack.

In the Year of Our Lord 1374, a deadly disease swept dozens of villages along the Rhine River — a dance plague. Hundreds of people on the streets jumped and curled their knees with no beat or music, except, probably, that in the dancers’ head. They danced, sometimes for many days in a row, until their broken feet refused to hold them. Many died of exhaustion, stroke or heart attack.

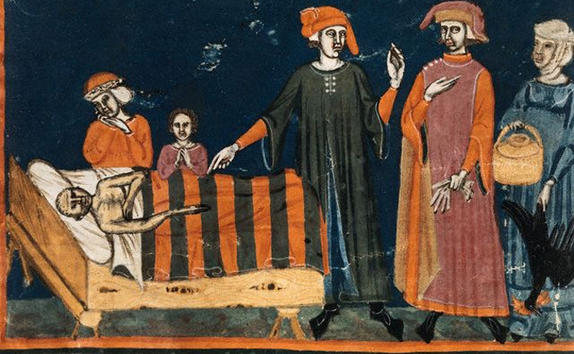

Another instance of the dancing plague (or dance epidemic or dancing mania) occurred in Strasbourg, Alsace, in the Holy Roman Empire in July 1518. Around 400 people took to dancing for days without rest and, over the period of about one month, some of those affected collapsed or died. Interestingly, the Strasbourg authorities first decided to let folks dance all they want, hoping for a spontaneous cure. Two dance halls were opened in the city and a wooden stage was erected. Musicians were also invited to liven up the strange event.

Interestingly, the Strasbourg authorities first decided to let folks dance all they want, hoping for a spontaneous cure. Two dance halls were opened in the city and a wooden stage was erected. Musicians were also invited to liven up the strange event.

Very soon it became clear that the measures undertaken did not lead to an improvement in the situation. In response, the authorities banned any and all entertainment in the city, save none, including gambling and prostitution.

Many theories were presented over time to explain the cause of the dancing plaque, most prevalent of which was severe food poisoning. The article in Wikipedia gives scientific names to every suspect poison.

John Waller, professor of the history of medicine at Michigan State University, does not agree with the poison version, however, since in both cases the symptom of the ailment was dancing rather than convulsions. In his book A Time to Dance, a Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518 Waller proposes his own theory: the dancing plague were of psychogenic (due to mental trauma) nature, and the main cause of this mass mental trauma were fear and depression.

The two outbreaks were preceded by famine, floods, loss of crop. The horror of the supernatural drew people into a state of trance. In such an atmosphere, it was enough for one madman of woman to start, and immediately infect hundreds of people around.

Drawing on fresh evidence, John Waller’s account of the bizarre events of 1518 explains why Strasbourg’s dancing plague took place. In doing so it leads us into a largely vanished world, evoking the sights, sounds, aromas, diseases and hardships, the fervent supernaturalism, and the desperate hedonism of the late medieval world.

At the same time, the extraordinary story this book tells offers rich insights into how people behave when driven beyond the limits of endurance. Above all, this is an exploration into the strangest capabilities of the human mind and the extremes to which fear and irrationality can lead us.

Filing stressed much? Fearful of floods, tsunami, hurricane, atomic war? Shall we dance?

Since the early Middle Ages,

Since the early Middle Ages,

Elizabeth of Thuringia

Elizabeth of Thuringia

They were created between 1616 and 1618 by Dionisio Minaggio, the chief gardener of the

They were created between 1616 and 1618 by Dionisio Minaggio, the chief gardener of the  There are amusing scenes of everyday life: a patient suffering in the hands of a dentist, a man playing a melody on a pipe, and waiting for his dog to “do her things” — musicians, artisans and actors, birds and plants.

There are amusing scenes of everyday life: a patient suffering in the hands of a dentist, a man playing a melody on a pipe, and waiting for his dog to “do her things” — musicians, artisans and actors, birds and plants.

At that time, Milan was ruled by Spain, and the Spaniards were familiar with the art of the pen widely practiced in Central and South America.

At that time, Milan was ruled by Spain, and the Spaniards were familiar with the art of the pen widely practiced in Central and South America.  Although the style and methods were very different, it is possible that knowledge about this art form served as inspiration. Still, this is only an educated guess.

Although the style and methods were very different, it is possible that knowledge about this art form served as inspiration. Still, this is only an educated guess. To this day, we do not have the faintest idea why Dionisio Minaggio created such an unusual for the time book, and who, if anyone, commissioned it.

To this day, we do not have the faintest idea why Dionisio Minaggio created such an unusual for the time book, and who, if anyone, commissioned it.

Voynich Manuscript

Voynich Manuscript

Boris Artzybasheff

Boris Artzybasheff

During WW II he served as an adviser to the Psychological Warfare branch. Why psychology? Wasn’t he an artist? See for yourself:

During WW II he served as an adviser to the Psychological Warfare branch. Why psychology? Wasn’t he an artist? See for yourself:

Each year the month of April is set aside as National Poetry Month, a time to celebrate poets and their craft.

Each year the month of April is set aside as National Poetry Month, a time to celebrate poets and their craft.

In 1310, in French town of

In 1310, in French town of

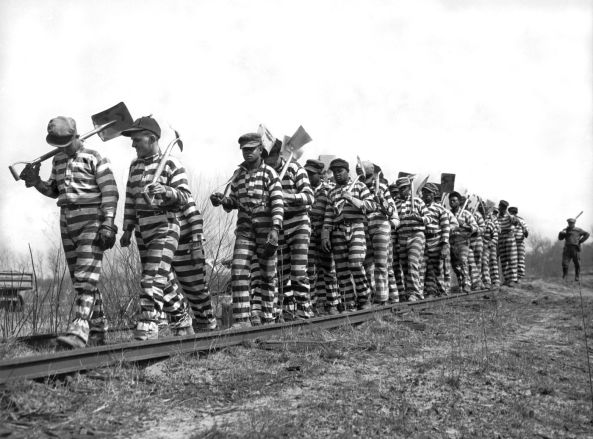

To this day, there is no consensus about the origin of stripes’ bad reputation. Pastoureau suggests that it came from the free interpretation of biblical quote Do not put on two tunics (Mark 6:9.) Another hypothesis, secular one, is more “practical”: striped clothing conceal the silhouette, and this alone could be regarded as an attempt of camouflage. However, neither the first nor the second hypothesis can explain the reasons for the medieval Europeans’ hateful attitude toward striped garments.

To this day, there is no consensus about the origin of stripes’ bad reputation. Pastoureau suggests that it came from the free interpretation of biblical quote Do not put on two tunics (Mark 6:9.) Another hypothesis, secular one, is more “practical”: striped clothing conceal the silhouette, and this alone could be regarded as an attempt of camouflage. However, neither the first nor the second hypothesis can explain the reasons for the medieval Europeans’ hateful attitude toward striped garments. Diabolical nature of strips extends to the striped animals as well. Not only black, but striped cats, tigers, snakes and hyenas were considered to have diabolical traits. Although in the Middle Ages only very few Europeans knew of the existence of zebras, Catholic naturalists ranked zebras as “devils of animals.” Unsuspecting zebras were relinquished to this category until the age of Reformation when the new generation of zoologists dispelled this belief.

Diabolical nature of strips extends to the striped animals as well. Not only black, but striped cats, tigers, snakes and hyenas were considered to have diabolical traits. Although in the Middle Ages only very few Europeans knew of the existence of zebras, Catholic naturalists ranked zebras as “devils of animals.” Unsuspecting zebras were relinquished to this category until the age of Reformation when the new generation of zoologists dispelled this belief. The strips shed its diabolical designation at the end of the XVIII century. Revolution occurred not only in France and the New World, but also in the minds of ordinary people. Stripes were no longer seen as taboo. A fashion for striped fabric, from clothing to furniture upholstery and walls, took off with vengeance.

The strips shed its diabolical designation at the end of the XVIII century. Revolution occurred not only in France and the New World, but also in the minds of ordinary people. Stripes were no longer seen as taboo. A fashion for striped fabric, from clothing to furniture upholstery and walls, took off with vengeance. However, in 19th century, coming a long way from the Middle Ages, the fear of stripes in society was embodied in the striped prison uniforms. Around this time, the black-and-white stripes familiar from old movies came into vogue, marking the men in a way that would remain embedded in public memory.

However, in 19th century, coming a long way from the Middle Ages, the fear of stripes in society was embodied in the striped prison uniforms. Around this time, the black-and-white stripes familiar from old movies came into vogue, marking the men in a way that would remain embedded in public memory.  Slowly, as time went on, prisons began to eliminate the stripes for more neutral colors and the familiar worker-like jumpsuits. New York switched to grey in 1904 because, according to an

Slowly, as time went on, prisons began to eliminate the stripes for more neutral colors and the familiar worker-like jumpsuits. New York switched to grey in 1904 because, according to an